The Christmas tree has been at the heart of our seasonal celebrations for centuries. Long before the advent of Christianity, evergreen trees and shrubs held special meaning for our ancestors in winter. Just as we decorate our homes with spruce, fir, holly, ivy and mistletoe, ancient peoples hung evergreen boughs over their doors and windows to ward off witches, ghosts, evil spirits, and sickness. Then, in 1846, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were sketched in the Illustrated London News, standing around a Christmas tree with their children, instantly reviving an ancient tradition. Nowadays, we simply appreciate a fresh-cut tree for its iconic outline and the wonderful scent of pine it brings into our home. Festooned with twinkling lights and decked with glittering baubles, nothing is so magical or uplifting.

My Six Top Tips

- Don’t buy too early. If you’re anxious about missing out on the perfect tree, keep it outside in a bucket of water until a couple of weeks before Christmas to make sure it’s as fresh as a daisy on the big day.

- Keep them cool. Bear in mind that a tree is already dead when you buy it, and natural processes of decay will accelerate in an indoor environment. Avoid positioning a real tree in a warm room or near a radiator. Heat will cause premature dulling of the foliage and speed needle drop. Bowls of ripe fruit close to a tree may have a similar effect.

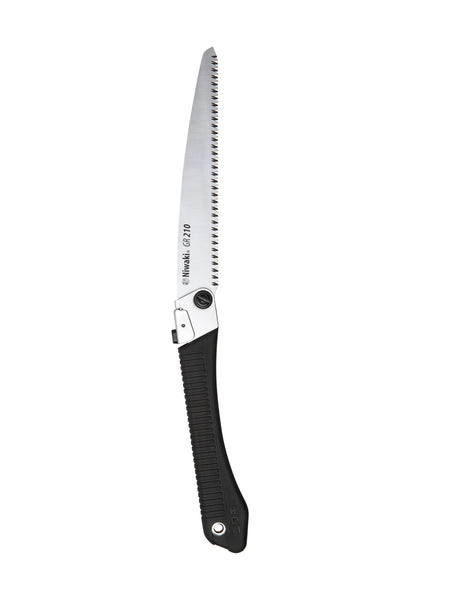

- Keep them moist. Always use a tree stand with a water reservoir. Sawing a couple of centimetres off the bottom of the trunk should facilitate water uptake, but I have found this doesn’t work unless the tree was recently felled. The main benefit of a water reservoir is that it creates humidity around the branches in an otherwise dry atmosphere.

- Wear gloves and a face mask. Using protective gear might sound like overkill, but many people experience an allergic reaction when handling a Christmas tree. Rashes and breathing difficulties can be caused by dust, pollen and mould spores attached to the foliage, a reaction to the tree’s sticky sap, or a response to the needles pricking sensitive skin. If you’re concerned about allergies, hosing your tree down and letting it dry in a garage or shed will remove most irritants. Wearing gauntlet gloves will prevent your hands and forearms from coming into contact with piercing needles.

- Let the branches settle. If your tree has been netted, the boughs may take a little while to drop back into position when unwrapped. Leave it overnight, or you can help by gently pressing down each branch and settling them into position. Remove any straggly or saggy branches with a sharp pair of secateurs.

- Burn your tree after Christmas - carefully incinerating your tree reduces emissions by 80% versus kerbside collection and composting. However, don’t burn Christmas tree wood in a stove, as the sticky resin can clog up your flue.

Choosing The Perfect Tree For You

Although artificial Christmas trees have become increasingly popular and realistic, I still prefer the real thing. Yes, they can make a bit of a mess, but they’re vastly more sustainable and characterful. Most artificial trees are manufactured in the Far East, with the dual environmental impact of being made from plastic, PVC and metal, before taking a journey halfway around the globe to reach our homes. Because of their complex construction, artificial Christmas trees can’t be recycled and go straight to landfill when they reach the end of their life. According to the Carbon Trust, a two-metre artificial tree has a carbon footprint of around 40kg, more than ten times that of a real tree burned after Christmas. (Statistically, the average artificial tree only lasts four Christmasses.)

Depending on the species, real Christmas trees take ten to twelve years to grow two metres. During that time, they provide a habitat for wildlife and capture carbon from the atmosphere. Most are grown here in the UK, with only a few being imported from overseas. 80% of those we buy are Nordmann firs (Abies nordmanniana), a tree species native to Turkey, Georgia and parts of Russia.

None of the common Christmas tree species is native to the UK, but when choosing a real tree it helps to think a little about the environment in which they grow naturally. Spruces (Picea spp.), firs (Abies spp.) and pines (Pinus spp.) generally hail from cool climates and high altitudes where they grow slowly on rocky terrain and impoverished soils. During winter, when they are not actively growing, conditions may be cold or freezing. Spruces, pines and firs are well adapted to challenging situations; hence many of the trees sold in the UK are grown in remoter parts of Scotland and Ireland, where they also benefit from high rainfall. Slow growth and lack of competition from other plants result in naturally bushy, well-shaped trees. When grown in warmer climates or rich soils, Christmas trees may grow faster, requiring regular pruning to encourage bushiness and the classic pyramidal shape.

I would always encourage you to buy local and certainly from UK growers to support British agriculture and lessen the environmental impact of transporting trees long distances. A UK-grown tree is also likely to be fresher, meaning brighter needles and perkier branches for longer in your home.

A Christmas tree’s penchant for cooler, wetter climes partly explains why they struggle with dry, hot interiors. Heat and lack of humidity may dull the needles and cause them to drop quickly, which no one wants. Bring your real tree indoors as close to Christmas as possible, if you can bear it. Until then, place it in a bucket of water in a dry, sheltered spot outside or in an unheated shed or garage. If you don’t have the patience (increasingly, people want their trees up and decorated at the beginning of December), keep the room as cool as you can and position the tree away from radiators and stoves. Use a stand that holds a reservoir of water, which you should top up daily. Don’t expect a tree to look tip-top for four weeks or more. It may soldier on if you choose the right one and treat it well, but one would not expect that longevity from a bunch of cut flowers, so why a large tree?

Potted trees are an alternative to a cut tree but are only useful if you have somewhere to grow them afterwards, which most of us do not. There are two types: ‘container grown’ have been grown in a pot for their whole life, and ‘containerised’ have been lifted from a field and potted for sale. Containerised trees will have lost most of their fine, feeding roots in the potting process and are unlikely to survive the ordeal of being disturbed and then subjected to heat. If kept watered, container grown trees may be planted out in late winter or early spring. A potted tree that drops its needles may re-shoot, so don’t give up hope if it looks like it’s had too many sherries on twelfth night.

Types of Christmas tree

Blue spruce (Picea pungens)

If you fancy a change, a blue spruce is about as cutting edge as you can get in terms of a real Christmas tree. The needles have a waxy coating, making them a very light, icy, bluish-green, often described as silver. When grown in good light, a blue spruce can be dazzling, especially when combined and contrasted with gold-leaved conifers. Slow-growing and expensive, blue spruces are typically sold as small, potted trees. Do not miss the opportunity to plant one out after Christmas and watch it develop into a magnificent specimen. Handle the blue spruce with care, as the needles can be extremely sharp.

Fraser fir (Abies fraseri)

One of the very best Christmas trees is the Fraser fir which is native to the Southeastern part of the USA. It is bushy and upright with soft, dark-green needles, and has a wonderful citrusy scent. It has been my tree of choice for the last five years, and I have found it to last a lot longer than a Nordmann fir brought inside at a similar time. The greatest advantage of a Fraser fir is that the branches are firmly ‘upswept’, meaning they don’t tend to droop under the weight of heavier baubles. They can be so dense that you might even find a discarded birds’ nest hidden inside! Needle drop is minimal.

Korean fir (Abies koreana)

Korean firs are rarely offered for sale in the UK, but they make splendid Christmas trees. Commercially they are extremely challenging to grow because they tend not to grow straight or on one central trunk. Larger specimens might have dramatic black cones, and the soft needles have an eye-catching, whitish underside.

Noble fir (Abies procera)

Another American native, the noble fir is starting to catch on here in the UK. It’s a statuesque tree with bluish-green foliage, a smart, conical outline, and few gaps at the top. Like the Korean fir, it’s tricky to grow; hence it can be more expensive to buy than other species. Needle retention is excellent.

Nordmann fir (Abies nordmanniana)

80% of us now choose a Nordmann fir (Abies nordmanniana), a fast-growing, chubby, large-needled tree. It’s the obvious choice, but there are better options. The secret is to buy one that’s been allowed to grow slowly and in splendid isolation to achieve a perfect shape. As with all fresh products, there are different grades available and this is reflected in the tree’s fullness and price tag. Expect the top quarter of the tree to be more open - hang your dangliest decs here to hide the gaps! While famed for its needle retention, the foliage does tend to lose its sheen quite quickly.

Norway spruce (Picea abies).

The only option when I was a lad, the Norway spruce is the tree we all fell out of love with after a deluge of prickly needles worked their way into our shag pile and the gaps between our floorboards. Tales of spraying trees with Elnett and finding needles for months have become Christmas folklore. Tall and graceful when mature, the Norway spruce remains the tree of choice for public spaces. It’s the handsome specimen that stands in Trafalgar Square and every other town centre in the UK at Christmastime. As a Christmas tree, it is an inexpensive choice, costing about half the price of a Nordmann fir ….. just have plenty of hoover bags to hand!